15.10.2016

Health risk in winter: modern building cunstruction often leads to a desert-like environment in living spaces

As the leaves begin to fall, indoor heating and temperatures start up again. A comfortable, dry, well-insulated home – that’s how we prepare ourselves for the onslaught of winter. But we are not alone in our homes: a multitude of viruses, bacteria and moulds are amongst us. Whether these pose a health risk depends on the room humidity and indoor ventilation, especially in winter.

As it storms and snows outside, pleasant temperatures inside represent comfort, so it is easy to conclude that the better we seal off our living space, the more quickly, cost-effectively and sustainably we will enjoy a comfortable indoor environment. A glance at a simple hygrometer would be enough to determine that the building theory for efficient heat insulation brings with it a side effect with significant consequences: the relative air humidity drops dramatically. Readings well below 20 per cent are common. As a result, artificial humidity conditions are created in the winter months that are comparable to the climate in Namibia, the Death Valley or the Sahara. This dry environment increases our vulnerability to infection. As an added detriment, many viruses and bacteria remain capable of infection for longer in low-humidity environments.

Pleasantly warm does not necessarily mean healthy

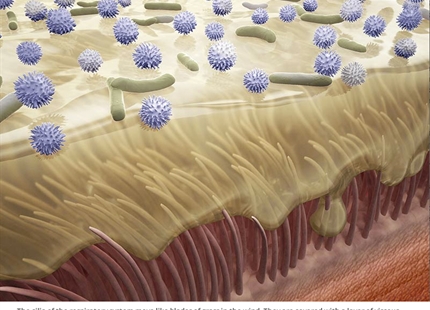

In winter, the dry indoor air places enormous strain on the body. The eyes and skin suffer, but the nose in particular faces the greatest challenge: it takes on primary responsibility for humidifying the incoming air and heating it to body temperature. Since we spend around 90 per cent of our time indoors with desert-like humidity levels, especially during winter months, it is only a question of time before the mucous membrane in the nose dries out.

Dryness in the indoor environment during winter can be attributed to the physical correlation between temperature and humidity: the warmer the indoor environment, the more moisture the air can absorb. But if the moisture supply stops, the relative humidity will continuously drop. In very dry winter air, the situation gets worse due to frequent ventilation. Effective action against this is limited to humidifying the air in the heated rooms, ideally in an independent and automated process. But the residential construction industry downplays the importance of sufficient humidity for health in many different ways. It is not a case of a lack of tried-and-tested technical solutions. For decades, for example, air-humidifying systems have been used around the world, incorporating all of the expertise gained over the years from a number of industrial applications.

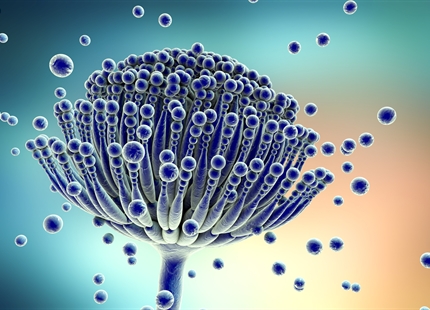

Catching cold in winter: dry indoor environments open the floodgates for viruses

The correlation between temperature and humidity often has disastrous consequences, above all in winter, when the outdoor air already has a low moisture content and the relative moisture content in heated indoor air drops to dangerously low levels. Sick people release micro droplets full of germs into the air when they breathe, speak and cough, which then evaporate in the artificial desert-like environment. The drastic release of moisture causes the salts in the droplets to crystallise. The germs are essentially preserved in the crystallised salt and can trigger an infection in someone else if they are breathed in and humidified again in the airways of a new person. The critical limit is at approximately 40 per cent relative humidity: below this point, the risk of infection increases as dryness in the air also increases. Above this point, the risk of infection is low because the germs are neutralised within minutes by the not-yet-crystallised, highly concentrated salt solutions.

Under natural conditions, this correlation represents a protective mechanism, but in our heated living environments it becomes useless. Worse still, the infectious viruses preserved by the dryness in the air have a relatively easy target thanks to the dried-out mucous membrane in the nose. This combination of elements becomes disastrous in light of the close quarters in which we share our air and therefore our germs. In the office, on public transport, in an airplane, etc. – there is hardly a place where we are not in close contact with others, so it’s no wonder that infections spread like epidemics in short time. Annual waves of flu are therefore not caused by cold outdoor temperatures, but by low humidity in heated indoor environments which keep viruses capable of infection for long periods and, at the same time, dry out the mucous membrane in the nose. The end of the story practically writes itself and tells of doctors’ practices filled beyond capacity and high levels of illness in the general population.

Numerous applications for air-humidifying systems – but rarely for people

The problem is literally home-made: with the focus on maximum building insulation (equivalent to airtightness), not only is the cold kept out, but so is natural humidity, which cannot be maintained indoors as a result. The accompanying day-to-day consequences are ignored – at least as it pertains to human beings, because a beef fillet gets more attention in this regard than an employee at a call centre. While the meat-processing industry has recognised the importance of sufficient humidity for assuring the quality of its products for a long time now, telephone operators in a large office continue to share the same dry air and its viruses. Similarly, luxury goods such as wine or tobacco are exposed to targeted humidity levels using specific technical functional systems during their processing, refinement or storage. Operating theatres and spas also take humidity into account when it comes to improving the well-being of the people who use them. The spectrum of potential applications has therefore not been fully utilised and remains a side topic right where humidity is of special importance for a huge number of people: the construction of residential buildings and workplaces. As a result, the construction industry fails to meet its primary aim: to offer people buildings that ensure protection and health. The condemnation of humidity as the source of all problems and, simultaneously, the high esteem with which total insulation from external influences is held, making it a benchmark for successful building, completely exclude the demands of the human organism. The building itself may be protected, but the needs of the people using the building take second priority. It is not crazy, then, to suspect that the growing number of patients with chronic lung disease, asthma and allergies can be attributed to the standards of the construction industry and the dogma of architects. In light of these consequences, a viral infection is the most minor problem faced by those affected.

Insulation and sealing helps with energy savings. Construction physiological findings are often ignored, so that the result is a deficient room climate.